Why Game-Making Is What Your Classroom Is Missing

Education is often divided by subject.

Engineers code. Designers design. Business students analyze. Artists create. That structure makes sense on paper. But outside the classroom, work rarely happens in neat categories. Real problems require people with different skills to work together, and meaningful learning should reflect that.

In our game-making programs, learners from engineering, design, business, marketing, administration, and communications worked side by side to build a single, playable game experience.

Why game-making naturally connects different fields

Making a game requires many kinds of thinking at once.

To create even a small playable game, teams need to consider:

- Story and characters

- Rules and logic

- Visual style and clarity

- Planning, time, and trade-offs

- Ongoing communication and teamwork

No one role can stand alone. If one part doesn’t work, the whole experience suffers.

That’s what makes game-making such a natural fit for interdisciplinary learning. Learners quickly see how their work affects others, and how progress depends on shared effort.

As one learner put it:

“Even though I wasn’t a programmer, my role mattered because the story and visuals shaped how the game felt.” Learner, Afterlight Studio (Design & Marketing background)

The Afterlight Studio team included learners from design, business, and engineering. Each person brought a different perspective, but everyone could see their contributions come together in one shared result: a playable game.

Structure supports creativity

Educators often worry that interdisciplinary projects might feel messy or unfocused.

What we observed was the opposite. These programs are intentionally designed to offer enough structure to support learners without limiting creativity:

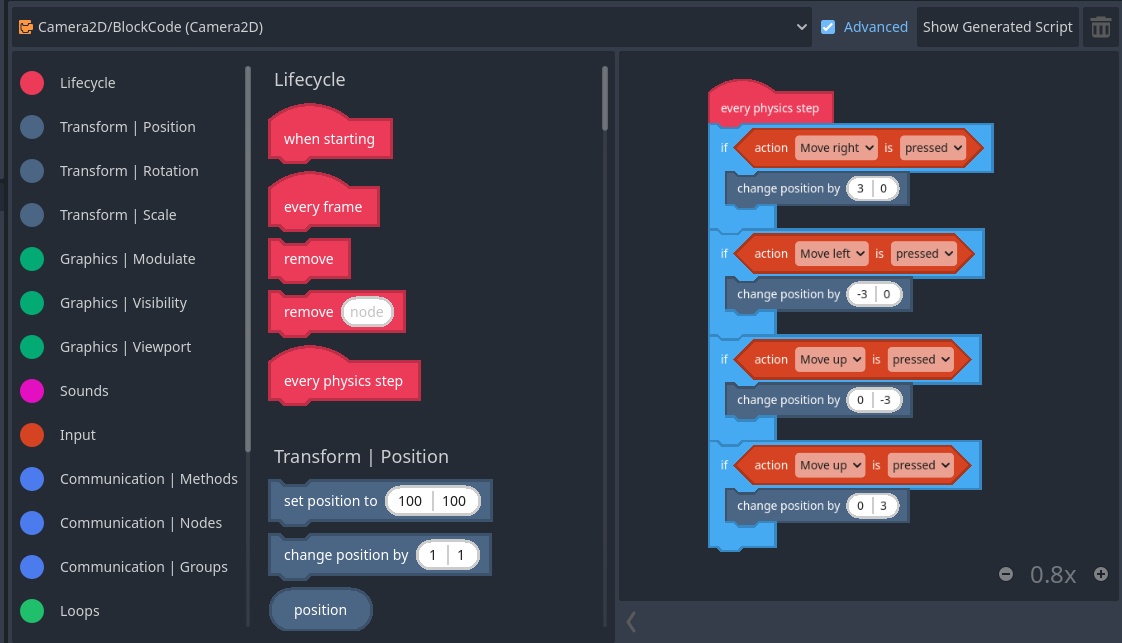

- Learners start with an existing game foundation instead of a blank page

- Creative choices come with clear boundaries

- Tools and templates reduce technical frustration

- Mentors guide thinking without giving step-by-step answers

The Gazzart Team reflected on how this approach helped them focus on meaningful decisions rather than just trying to get something working.

“Having a base game meant we could focus on decisions, not just setup.”

— Learner, Gazzart Team

When structure is thoughtful, learners spend less time stuck and more time thinking deeply about their choices.

From “my task” to “our game”

One of the most noticeable shifts happened early on.

Teams stopped thinking in terms of majors or assigned roles and started thinking in terms of what the game needed next.

Instead of asking,

“What am I responsible for?”

Learners began asking,

“What’s getting in the way of the game right now?”

That change matters. When learners feel responsible for a shared outcome, participation becomes more balanced and engagement grows. The Marci Team described this clearly. With members focused on programming, story, art, and design, progress depended on constant conversation and adjustment.

“We had to explain our ideas in a way everyone could understand — that’s when things really started clicking.”

— Team member, Marci Team

Rather than splitting work into disconnected pieces, teams learned how to connect their ideas — a skill that carries directly into real-world workplaces.

Feedback becomes immediate and concrete

Another strength of game-making is how clear feedback becomes.

Instead of abstract comments, teams can point directly to what’s happening:

- A mechanic that feels confusing

- A moment that doesn’t communicate clearly

- A scene that doesn’t have the intended impact

The Neon Glitch Studios team described how playtesting made problems obvious — and encouraged the team to solve them together.

“When something didn’t work, we could see it immediately when we played the game.”

— Learner, Neon Glitch Studios

Because the work is playable, learners are more willing to revise, adjust, and try again. Iteration feels natural, not like failure.

Why this matters for educators

Game-making isn’t valuable because learners become game developers.

It’s valuable because it:

- Reflects how real teams work

- Requires communication across different skill sets

- Makes trade-offs visible

- Turns learning into something tangible

- Encourages revision instead of perfection

When learners build something together that others can experience, learning becomes more durable and transferable. Game-making simply makes these learning principles easier to see — and easier for students to care about.

How these programs are designed

These outcomes don’t happen by chance.

Across our game-making programs, we intentionally design experiences that:

- Center learning around real, playable work

- Bring together learners with different strengths

- Balance freedom with clear expectations

- Build in time for testing, feedback, and reflection

- Treat learners as contributors, not just participants

Where this leads

The teams featured here didn’t just complete a course.

They experienced what it feels like to build something meaningful with people who think differently than they do.That kind of experience, learning how to collaborate toward a shared goal, is becoming essential in education and beyond. For independent educators, our game-making materials can be downloaded and used in classrooms, afterschool programs, or community spaces.

For schools and partner organizations, we work together to adapt these experiences to different schedules, learners, and contexts.

👉 Download game-making facilitation materials

👉 Get in touch to explore collaboration

.jpeg)

.png)

.png)

.png)