How Open-Source Game Development Is Transforming How We Teach Digital Skills

How community-built games can help young people gain real skills, and why educators should care

At this year’s GodotFest, our team had the chance to talk about something we deeply believe in: game development can, and should be more accessible.

On stage were Sarah Spires and Will Thompson from our Game Design team introduced a new way of thinking about teaching game development, one built on openness, shared creativity, and genuine community.

You can watch the full talk here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3znz3-15g8Y

The Problem We See Every Day: Young Creators Aren’t Getting Real Opportunities

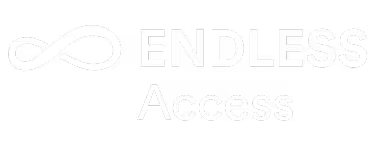

Sarah opened with an honest look at the games industry:

“Entry level isn’t really entry level anymore.”

Most “junior” roles expect 2–3 years of experience. Meanwhile, schools graduate thousands of game-enthusiastic students every year who never get a chance to build that experience in the first place.

For educators, this probably sounds familiar. Many young people:

- Can’t take unpaid internships

- Don’t live near game studios

- Don’t have access to expensive software

- Don’t have mentors in their local community

And even if they do get to work on real projects, juniors and interns often go uncredited, which makes building a portfolio even harder.

The end result? A huge amount of talent and creativity gets stuck at the door.

Our Argument: Community-Built, Open Source Games Can Change That

This was the heart of the talk. Will explained why we believe in a different approach:

“Anyone with a computer and internet access can join. There’s no interview gauntlet.”

Instead of asking young people to fight over one internship, we invite them into a living, breathing open-source game project where their contributions are:

- Visible

- Valued

- Credited

Not as a simulation. Not as a “school assignment.” But as actual work on a real game.

The game we’re building is called Threadbear, a top-down narrative adventure made with the Godot engine. It’s designed from the ground up to be contributed to by learners of all skill levels. But the important thing is not the game itself. It’s the model:

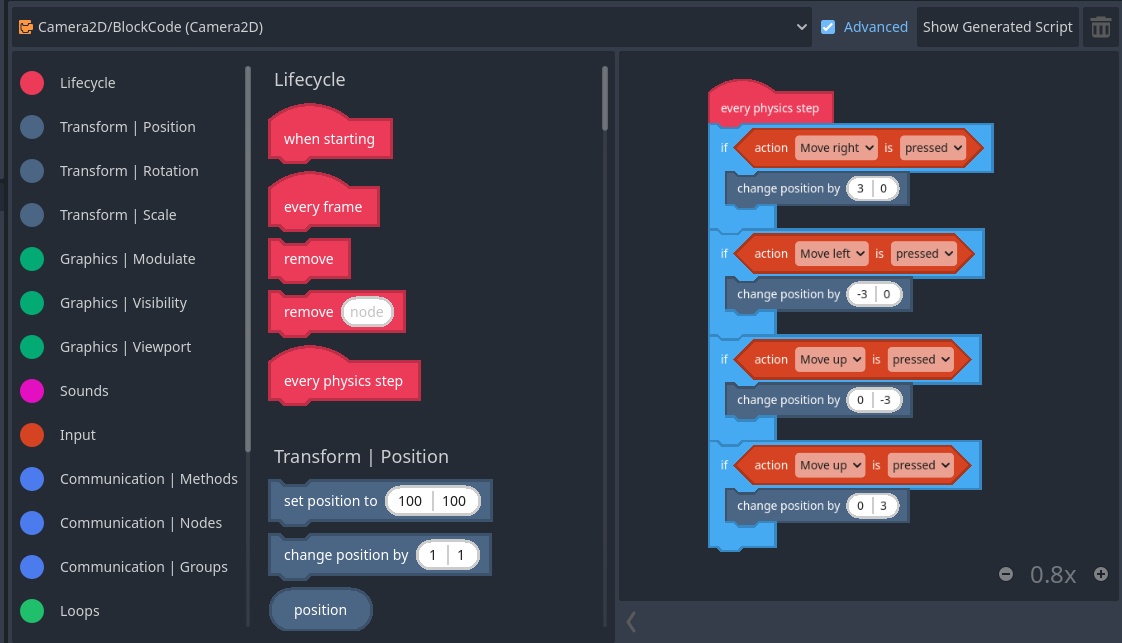

- Real tools (Godot, Git, real pipelines)

- Real mentors

- Real contributions that make it into the actual game

- A supportive community

For educators, this means your students’ work doesn’t disappear at the end of the semester,

it becomes part of something meaningful, visible, and lasting.

How We Structure the Project So Students Can Actually Succeed

One of the most common concerns we hear from educators is:

“This sounds great, but how do beginners actually participate?”

Here’s what we shared:

1. Everything is public

We keep our code, our ideas, our task lists, and our design decisions out in the open. It teaches transparency and lets students see how professional teams collaborate.

2. Tasks are clearly marked by skill level

Some tasks take an hour. Some take a week. Some require code; others don’t.

This lets students build confidence step by step.

3. Templates help students create quickly

We provide ready-made scenes, dialogue tools, animations, and more. This means students can focus on creativity instead of wrestling with technical setups.

4. All contributions count

We make space for:

- Concept art

- Bug reports

- Dialogue writing

- Paper level designs

- Playtesting

- Full quests

- Custom scenes

Educators love this because it’s easy to connect to multiple subject areas, writing, art, coding, storytelling, and teamwork.

Real Student Work: A Few Examples We Showed

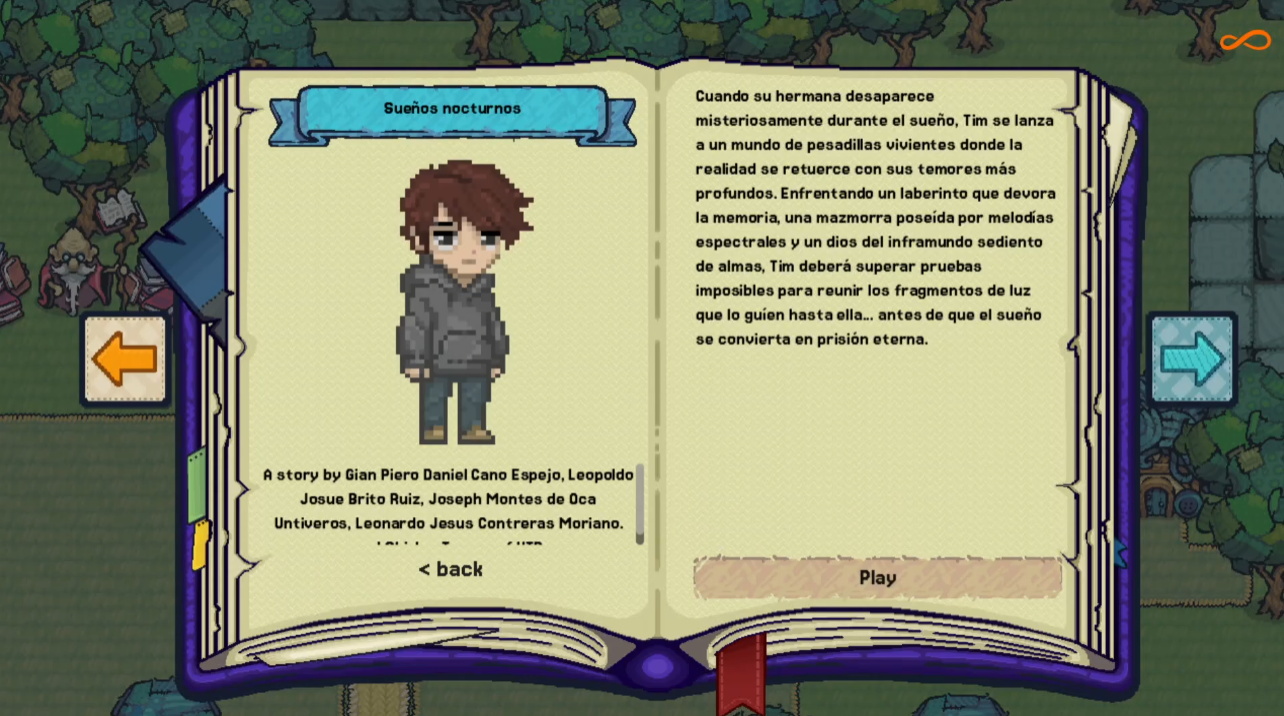

During the talk, Will shared some learner creations already inside Threadbear:

- A surreal “homework gone wrong” quest

- A spooky nightmare story with custom art and animations

- A sci-fi tale about culture and technology colliding

- Peruvian wildlife-inspired creatures

- A fan-fiction-style “lost toy” adventure

One student even started with a single drawing, and now their creature is becoming a full enemy in the game, complete with movement, animations, and behaviours.

These aren’t hypothetical classroom exercises. These are published contributions in a real project.

What We’ve Learned (And What We’re Still Learning)

We didn’t sugarcoat things. We shared the challenges too, because educators face them every day:

What worked well:

- “Playable documentation” examples that can be experimented with

- Small, self-contained tasks

- Clear scaffolding

- A friendly Discord community for asking questions

What surprised us:

- Some Godot behaviours confuse beginners (for example, changing one tileset can accidentally change the whole game)

- Too many templates can unintentionally limit creativity

- Large, multi-chapter quests are often too much for early contributors

- Licensing is trickier than expected (many “free asset packs” can’t legally be redistributed in open-source projects)

For educators, these lessons translate to:

Start small, celebrate progress often, and give students guardrails, but not walls.

Why This Model Works So Well for Educators

In short, because it connects learning to real outcomes.

Students don’t just learn concepts. They build things. They publish things. They gain confidence because their work matters to someone beyond their classroom. And because Godot runs on almost anything, even old laptops, there’s a very low barrier to entry.

How Educators Can Get Involved

At the end of the talk, we invited the audience to try Threadbear and join the community:

- Play the game (even in your browser)

- Explore the open repo

- Use our free learning materials

- Bring students to the community

- Ask questions or get support in Discord

- Build something together with your class

We believe this model can help the next generation of developers, storytellers, and artists find a real pathway into tech and creativity, especially those who rarely get the chance.

You can learn more about our programs here!

.jpeg)

.png)

.png)

.png)